Monday 7 November 1966

“The Dead Sea Fruit” Writer Peter Draper Directors Dennis Vance & John Cooper.

“I've decided to do something more intelligent with my money than underwrite my husband's ambition..” Pamela Wilder

After the laid back amusement of “The Big View”, Peter Draper follows up with the sucker punch of “The Dead Sea Fruit”. Pamela Wilder (Barbara Murray) tires of her husband’s indifference and withdraws her capital from Elberdson’s Merchant Bank.

While waiting for Wilder to arrive home one evening, Pamela is challenged by old friend Esther Keir (Elizabeth Sellars) over her unrealised ambitions. She asks when was the last time Pamela visited an art gallery or the theatre.“When you were 18 you told me you wanted to marry a man who was intellectually your superior and who wanted to leave some small part of the world different from how he found it. Whose hair fell over his eyes. Who had crinkled and bewildered eyes like Henry Fonda. Who was creative. Gentle. Fond of children. Sexy and six foot ten.”

As if acknowledging that only the first quality could describe Wilder, Pamela resignedly tells her that, “Men who are your intellectual superior soon get tired of having to slow down to speak to one.”

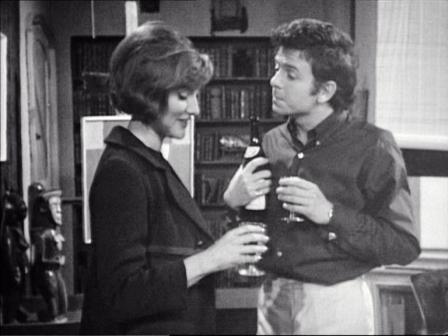

After a preoccupied Wilder returns home and barely acknowledges her, Pamela spends the next day at an art gallery where artist Andrew (Ray Brooks) chats her up. Inspired, with the thought of opening an art gallery, Pamela visits Sir Gordon Revidge and tells him she wants to withdraw her money from Elberdson’s Merchant Bank. This money supports Wilder’s position at Bligh Construction and the Merchant Bank. The fact that Wilder rushes home at mid-day after previously ignoring her only increases her distress. “You neither love me nor want me. What brought you home just now was the money.” But Pamela is still uncertain whether to leave him, and she only decides to walk out when a coincidence makes it seem that Wilder is still seeing Susan Weldon.

“The Plane Makers” episode “Loved He Not Honours More” established that Pamela Wilder had given John Wilder the £3000 deposit on their house in exchange for shares in Scott Furlong. Over the next ten years, the shares had increased in value to a quarter of a million (1964) pounds. Following the work of her financial advisor Mr Telliter (John Wentworth) in that episode, Pamela had become the largest shareholder in Scott Furlong (Elberdson’s Merchant Bank had previously held a 27% controlling interest). In this episode we see the unexercised power it gives Pamela.

This episode also revisits “The Plane Makers” episode “Sauce For The Goose” by David Weir. Then it was Georgina Cookson as a “man-hungry” friend who introduced Pamela to young American Al Bonners (Murray Hayne). That episode concludes with Pamela telling Wilder that “I wanted to pay you back – but couldn’t…if he had been any less of a nice person I would have slept with him.” To which Wilder replies, “Then you might as well have done.” In “The Dead Sea Fruit” Pamela refuses the overtures of young artist Andrew. She also tells Frank Hagadan (George Sewell) that if she does leave Wilder, “I won’t be leaving him…just to go away with someone else. I want to find out what happened to me.”

The centrepiece of this episode is a massive confrontation between Pamela and Wilder when Sir Gordon tells him that Pam has decided to remove her capital from the bank. Barbara Murray is in her bedroom emptying the contents of her day handbag into her evening handbag when Patrick Wymark enters, still wearing his overcoat. Fixing her with a narrow-eyed glare, he closes the bedroom door behind him and advances slipping his hands into his pocket (“the Wilder walk”.)

As they start the conversation about the money he walks around the bed and then explodes in exasperation, “For God’s sake Pamela, this is a business matter! Why do you have to drag your stupid emotions in?”

A raft of emotions pass over Barbara Murray’s face; “Why the hell do you think I’m taking my money out if it isn’t because of emotions? Do you think they’re any less important than money? Oh God, John, I’m sick of you believing that the only important problems are those to do with money!”

Wymark adopts a calmer, rhetorical stance and asks, “WHY?” Barbara Murray smiles in a challenging manner, as if listing reasons she’s gone over a hundred times in her head. “Not just because we had a ‘silly row’ the other night. Not just because I hardly ever see you. Not just because the only time you ever do come home is when you want me to do something for you.”

Wymark turns away, pacing to the side as if trying to avoid the accusations. He wags his finger in exasperation as if telling off a child. “Do you realise the incredible trouble this is going to cause?”

Barbara laughs, eyes narrowed, squaring up to him. “Yes I do. I realise exactly what incredible trouble this is going to cause. I can do ANY SILLY THING I LIKE. I’ve decided that I can’t go on like this.”

Deflated, Wymark sits on the bed as her realises she is talking about leaving. For the first time he looks scared. Barbara Murray stands with her back to her immaculate fitted wardrobe. “You neither love me nor want me. What brought you home just now was the money.”

Wymark closes his eyes regretfully. He gets up and walks round to put a hand on Barbara’s shoulder. She flinches away (“No, John please don’t touch me.”) but he continues putting his other hand on her right shoulder and trying to draw her towards him (“Let’s forget about it. Let’s go..”). Barbara pushes him off shouting, “Leave me alone! I’m sick of being a possession of yours!” She begins crying.

“I’m sick of you coming home from another woman’s bed. I lie there and I know where you’ve been. You stink of her scent. The smell of it’s all over you. I lie there and I say to myself, what am I for?”

In his film, “Mr Arkadin” Orson Welles * popularised the fable of the Scorpion and the Frog with its punchline “It’s my nature”. The fable comes to mind at the end of this scene when Wilder says, “We’ve got to talk about this seriously some time…if only about the money.” His self-defeating response finally reduces Pamela to hysterical laughter. At the end of the episode when Pamela is packing to leave, Wilder stands bereft in the bedroom, fingering her powder compact like it’s a precious thing. Pamela she’s not taking the compacts and Wilder says hopefully that she can always come back to collect it later. And then Wilder says, “Pamela – what are you going to do about the money.”

The episode title is justified by Ken Bligh (Peter Barkworth) who recalls Andre Abina telling him in “Ambassador Status” that, “Power is like the Dead Sea Fruit. When you achieve it, there is nothing there.” Although the loss of Pamela’s capital would destabilise Wilder’s position at Bligh Construction, Ken is wary of his father coming back to take control of the company. He acknowledges that Wilder has built the firm up and is willing to support him against Caswell (at least until his own position is more secure).

“The Dead Sea Fruit” benefits from two strong guest performances. Elizabeth Sellars as the three-times married, three-times divorced Esther Keil is a plausible catalyst for Pamela’s frustration although the “terrifying” young girls at Esther’s boutique (“Like a race of barbarians. And all so confident”) remind her that starting again would be a challenge. And Elizabeth Sellars’ wheedling phone call to her younger boyfriend conveys the insecurity of her freewheeling life. The Glasgow-born actress had appeared in the Royal Shakespeare Company production of “The Taming of The Shrew” with Patrick Wymark, Peter Jeffrey and Ian Holm. She also appeared in “The Barefoot Contessa” (1954) and had just completed filming on Hammer’s last production at Bray, “The Mummy’s Shroud” (1967).

Ray Brooks, playing hot young artist Andrew had starred as womanising Tolen in Richard Lester’s “The Knack” (1965) and his casting may well have led viewers to expect that this time Pamela really would pay Wilder back for his infidelities. But Andrew is arrogant and written to show up Pamela’s strengths. In their first encounter at his art show, he asks if she’s a “viewer or a lover”. She replies , “that contains all the available choices – detached or participant” before confirming that she’d prefer to be a participant. Andrew compliments her on the fact that she was actually looking at the paintings, while the other viewers have their backs to the paintings. “They’re telling each other how lovely they are and how cleverly their minds work. Later on they’ll buy a painting because they love art and because they hope to god the value goes up.”

When Pamela calls at Andrew’s flat to discuss setting up a gallery, he assumes she has other motives and decides to cut out the small talk.“You’re not the first long married lady who’s been round here. You know, suddenly in the middle of the evening, nothing to do. Why not phone up the bohemian young man. Have a look at a few pictures and who knows, have a little adventure. Very strange. It’s always around 9’O’Clock at night, Maybe that’s when their own hubbies are whooping it up.”

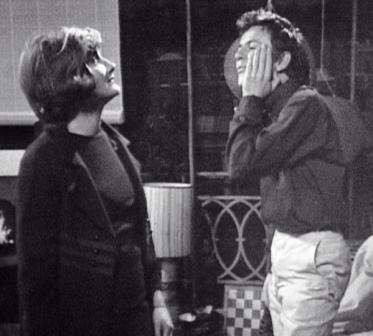

Ironically, although she told Wilder she would have slept with Al Bonner if he had been less of a nice person, it’s Andrew’s obnoxiousness that seems to earn him a slap round the face. Bearing in mind her earlier aversion to the “confident..barbarian” girls in Esther’s boutique, it’s probably not surprising that when Andrew says “I shouldn’t think a woman’s done that to a man since your generation”, Pamela gives him another slap saying, “it’s an awful pity that your generation’s had to cop the lot.”

Although Ray Brooks is appropriately condescending and arrogant in this role, the following week, would see a totally different role in the ground-breaking BBC Wednesday Play “Cathy Come Home” – Ken Loach’s expose of homelessness in Britain.

Hendersonwatch: It seems Don Henderson’s marriage is still intact. When he arrives to collect Wilder for work he says, “Oh Pat wants me to tell Pamela something…”

*Orson Welles would star opposite Oliver Reed as advertising boss Jonathan Lute in “I’ll Never Forget What’s Isname (1967) written by Peter Draper, directed by Michael Winner