CHILDREN OF THE DAMNED (1964)

During a United Nations study of child intelligence, London University psychologist Tom Llewellyn (Ian Hendry) is astounded by child genius Paul (Clive Powell). Senior lecturer in genetics Dr David Neville (Alan Badel) wants to find out more about Paul’s background but when his mother (Sheila Allen) tells him “I should have crushed you at birth”, the child compels her to attempt suicide.

As the United Nations identify five other children from around the world with intelligence equal to Paul, Colin Webster (Alfred Burke) of British Intelligence moves in to “protect our asset”. The children escape to an abandoned church in East London and violently resist all attempts to control them. As the army moves in to destroy the children, Tom Llewellyn makes a desperate attempt to protect them.

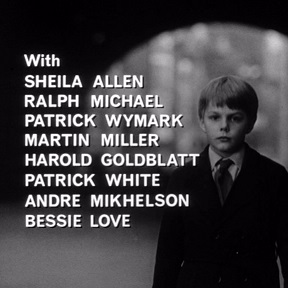

The movie has strong lead performances from Ian Hendry (The Avengers, Get Carter) and Alfred Burke (Public Eye, Harry Potter & The Chamber of Secrets), although it is Alan Badel as the cynical geneticist who delivers the best of Briley’s lines (“Somebody really ought to do something about religion in this country,” he says as he regards the bomb-damaged abandoned church (St Dunstan’s in the East) in which the children make their base). Patrick Wymark makes a late appearance towards the end of the film.

This 1964 sequel to “Village of the Damned” (1960) is an original screenplay by John Briley, a former staff writer at MGM who went on win an Oscar for his screenplay for “Ghandi”.

The credits refer to the film as a sequel to “The Midwich Cuckoos”, perhaps mindful that John Wyndham had attempted an abortive sequel - “Midwich Main” – at MGM’s behest. However, Briley’s script makes no reference to “Village of the Damned” and can be viewed without any knowledge of the previous movie. While it’s possible to speculate that the UN study was purposely seeking further outbreaks of “cuckoos”, speculation within the movie suggests the origins of the children could be unrelated. Director Anton Leader (who as Tony Leader directed The Twilight Zone and Hawaii 5-0) drives the move forward forcefully but still leaves room for speculation as to where the story is heading. Early on, Ian Hendry asks the children why they’re here and they answer, “we don’t know.”

Towards the end of the movie – surrounded by soldiers armed with rifles and rocket launchers – a UN representative repeats “What is your purpose – why are you here?” This time, lining up in front of the soldiers, the children have an answer: “For the same reason you are. To be destroyed. You may choose your way. We have chosen ours “

Earlier on, Badel had warned Hendry, “Either we control them or they control us. It’s the law of nature, Tom. Ask any ape.” The implication is that the children – whatever they are – find freedom more precious than life. Earlier on, Badel’s character had questioned the Government’s ambition to exploit the children’s advanced scientific knowledge, “Suppose all they want to be is poets, or lovers, or even tramps.” But having seen them resist attacks with mind-control and a mysterious sonic weapon, Badel is swayed to the government’s side. “They could be controlling a bomber up there, ready to press the button!”

In a similar vein Hendry asks Burke’s intelligence agent, “What the hell would you do if all the great powers suddenly smiled at each other; had a great love affair?” Burke deadpans, “I wouldn’t worry too much. You know how love affairs go.”

Patrick Wymark only appears in the last fifteen minutes of the movie as the General in charge of the army unit surrounding the children. The role marks a crossover – filmed before he assumed the role of John Wilder in “The Plane Makers but released in April 1964 after the series had made Wymark a star. He carries out the role with quiet authority, rather than the stereotypical psychopathic behaviour which military officers display in more recent science fiction movies. Wymark’s entrance comes at a crucial point after the children have wiped out most of the politicians who seek to control them. Leader devotes extensive footage to the procedures of the engineers as they rig explosives and test circuits. “I want plenty of distraction, “ Wymark tells his men, Keep those vehicles moving til we’re ready.”.

Even in its final moments, there is some ambiguity about “Children of the Damned”. A technician accidentally closes a circuit, triggering a final assault. On first viewing it seems as if the ending is just a terrible mistake. But is it actually a final piece of mind control by the children? Curiously, the film has as much in common with Briley’s 1978 adaptation of Peter Van Greenaway’s novel, “The Medusa Touch”. Both feature scenes in which a child uses telepathic powers to threaten his mother after she has criticised him. Both display a curious ambiguity – Richard Burton in “The Medusa Touch” questions why he has been given his powers which always seem to result in disaster, while the spokesperson for the “Children of the Damned” admits that they have no plan.

“Children of the Damned” might also seem like a precursor of “The Omen” – certainly the baleful glare of Harvey Stephens as Damien in “The Omen” echoes the furrowed brow of young Clive Powell – Paul in Children of the Damned. The helpless terror of the scene where Paul’s mother (played by Sheila Allen) seems to dream her suicidal walk into a road tunnel is very similar to the self-destructions in “The Omen”. Although Allen survives, she is hospitalised - bandaged and encased in plaster in a way that visually anticipates Lee Remick towards the end of the 1976 movie. Allen’s cries of, “He isn’t mine! I gave birth to him but I hadn’t been touched! He hasn’t got a father!” are also reminiscent of the speculation about Damien Thorne’s parentage.” Damien’s canine familiars also echo the faithful, snarling sheepdog which accompanies the children to their abandoned church.

If there are similarities between “The Omen” and “Children of the Damned” though, the main difference seems to be that Damien follows a scheduled rise to power, aided by a coven of supernatural groupies, while the Children of the Damned, are lost and bewildered, unsure of their purpose until the very end.