Doppelganger - aka Journey to the Far Side of the Sun

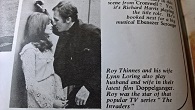

Doppelganger (1969) – better known as “Journey To The Far Side of the Sun” - stars Patrick Wymark as Jason Webb, project director of Eurosec (European Space Exploration Complex). Set in the 21st Century, the film deals with the discovery of a planet in an opposite orbit to Earth on the far side of the Sun. Scripted by Donald James, the film was based on an idea Gerry and Sylvia Anderson had for a “Twilight Zone” style TV play for ATV’s “Armchair Theatre”. Gerry Anderson later took the idea to Universal when the studio set up a British production office in 1968.

Patrick Wymark with Ed Bishop as NASA liaison David Poulson and George Sewell as security chief Mark Neumann

Doppelganger is part of the small sub-genre of “Space Race” movies produced during the window of perception when the public gradually realised that this crazy space stuff was really going to happen, but while there was still a great deal of suspense about what the astronauts might find when they landed on the Moon. While “Countdown” (1968) and “Marooned” (1969) went for semi-documentary realism and dealt with the physical risks of the mission, “2001: A Space Odyssey” (1968) and the Anderson’s own “Thunderbirds Are Go” (1966) provided alien menace, even though it was more subtle than the men in monster suits of earlier science fiction films.

Doppelganger shows the discovery of a planet in the same orbit as Earth but on the opposite side of the Sun. Wymark’s character sends astronauts Ian Hendry and Roy Thinnes on a six week journey to explore the counter-Earth. Their ship returns three weeks early and crash-lands back on Earth. Thinnes is suspected of sabotaging the mission but gradually realises that everything on Earth is now reversed. Or rather – everything on the other Earth is reversed. The mission did get to the counter-Earth, where life has developed in parallel – except for being reversed!! As the posters for Doppelganger put it – “Are you two people reading this poster? Is there another you…on the far side of the Sun?”

Roy Thinnes explains his theory of the mirror image world to Patrick Wymark

Publicity for the movie unashamedly describes Patrick Wymark’s character as a “21st Century John Wilder”. Since the Andersons were fans of “The Plane Makers” and “The Power Game” it’s possible that Wymark may have been in their thoughts even during the earliest concept of a TV play. Certainly, the initial treatment by Tony Williamson (scriptwriter for the Plane Makers episode“A Condition of Sale “) described Webb as “about fifty, stocky, medium height, but with a personality that radiates power. …He can be extremely smooth, but…never fails to leave the impression that the most charming phrase has a knife edge to it.” (1)

The similarity between Webb and Wilder was further emphasised by casting Norma Ronald, who had played Wilder’s secretary Kay Lingard, as Webb’s secretary Pam Kirby.

In “The Plane Makers” (“Don’t Stick Your Head Out “) there had been speculation about Miss Lingard’s relationship with Wilder, and early drafts of Doppelganger depicted Pam Kirby “working late” in a “semi-transparent negligee”. These scenes implying an affair with Webb seem to have been dropped as part of negotiations with the British Board of Film Censors (2), although it’s interesting that the Anderson’s chose the forename of Wilder’s TV wife (Pamela Wilder) for Webb’s secretary.

Webb also shares John Wilder’s talent for game-playing and politics. The first twenty minutes of the movie show the fight to win funding for the space mission. When NASA liaison Poulson (Ed Bishop) and the Eurosec Council refuse to finance the project, Webb allows suspected spy Herbert Lom to access information about the new planet. Lom’s exposure panics Poulson, who realises that an enemy power may get to the Counter-Earth first and he recommends that NASA fund Webb’s mission. Webb’s actions reflect Wilder’s game playing - although murder was never sanctioned in “The Plane Makers” (Webb tells his security chief that if Lom “…shows his hand, I don’t want an arrest.”) Sadly, the political aspects were scaled back for the final shooting script due to concerns that too much detail would turn off audiences. A comment in the draft script says Webb’s proposed budget of three thousand million pounds is just a starting figure that the other countries may agree to and be unable to back out from when costs escalate. (3) That is very reminiscent of the road construction costings in “The Power Game” and the budgets for the VTOL project in the last series of “The Plane Makers”.

“The Power Game” was made when Britain was still outside the European Economic Community but anxious to crack the export market (with Wilder made a temporary envoy to Europe at the end of the first series). EUROSEC is reflective of the six members of the EEC, although in a stroke of wishful thinking, Luxembourg’s seat on the council is replaced by Britain. The structure of Eurosec also represents the economic structure which would form the background to the final series of “The Power Game”; Germany and France lead the organisation, with Germany being the voice of financial conservatism and France hostile towards the British plans. America’s economic dominance is reflected in the fact that although the USA is not a member of the organisation, the NASA liaison swings the deal at the cost of having an American astronaut leading the mission.

The one un-Wilder-like aspect of Webb’s character is a burst of “Little-England” dialogue when Webb shouts, “Trust a German to louse it up.” This had been watered down from James’ draft script where Webb had objected to being “dictated to” by “the Germans, who we defeated inn two world wars.” In the TV Show, Wilder rarely voiced prejudice and would sell to or work with any country so long as he was on the winning side!

Director Robert Parrish frames George Sewell in a mirror as he talks with Patrick Wymark - a subtle clue to the fact that Thinnes has arrived on a reversed world.

Another “Power Game” crossover is the casting of George Sewell as security chief Mark Neuman. Sewell had played engineer Frank Hagadan, the lover of Pamela Wilder, in the first two series of “The Power Game” but here plays a quite different role. Neuman seems unconcerned when Webb says he doesn’t want Herbert Lom’s spy character arrested and coldly shoots him down. Neuman’s actions anticipate those of the homicidal space agency in Peter Hyam’s “Capricorn One” (1977) which will go to any lengths to ensure its budget is not cut. Surprisingly, while the British Board of Film Censors was opposed to showing a feminine contraceptive, and anxious about the amount of blood during Lom’s shooting, there was no concern about the head of a non-Government body authorising his shooting. (4)

While the concept of the mirror world is often derided, it’s fair to say that if such a world did exist it would have tremendous implications, not least for the idea of free will and destiny. Webb admits that he discounted computer data because he didn’t want to believe it. Once Hendry’s character dies, an autopsy shows that his organs are reversed. Although Thinnes convinces Webb of his theory about the counter-Earth, the only way they can prove it is for Thinnes to return to the mother-ship “Phoenix”, still in orbit around the Earth. In their initial draft, the Andersons had ended on a speculative note – would Webb authorise the mission. In the movie, Thinnes returns to the “Phoenix” – the writing on the engine logos’s in “the right way round” confirming that it’s from our Earth – but then his shuttle (a duplicate built on the counter-Earth) is rejected by the systems. Thinnes shuttle crashes back into the Eurosec space centre, killing everyone except Webb.

Unfortunately, not only is the outcome depressing, but the reason why things go wrong is confusing. Thinnes loses radio contact with mission control due to the electricity mismatch and this means he can’t talk it through with Wymark for the benefit of the audience. After multiple viewings it becomes easier to get a handle on what went wrong, but it’s easy to imagine 1969 audiences scratching their heads and leaving the cinema as confused as they were at the end of “2001”.

Speaking of “2001”, many commentators have speculated that the production tried to mimic the end of “Stanley Kubrick’s” film. With all records and proof destroyed, an aged and broken Webb is shown in a care home. A nurse is worried about his heart and wheels him inside looking for help. She leaves him in an ornate corridor where, dressed in a burgundy dressing gown, he stares at his white-haired reflection. The vacant look is replaced by determination and he propels his wheel chair towards the mirror. The sound of breaking glass accompanies a subliminal shot of green fields. The scene is generally interpreted as Webb’s death, although it’s notable that Barry Gray’s score builds to a short triumphant reprise of the Doppelganger theme as Webb sees his reflection and wheels himself towards it. It’s worth noting that Tony Williamson’s original treatment ended with the astronaut deciding not to go back into space after his wife says, “with the kind of logic only a woman could have…that there just isn’t any point in going two hundred million miles… to look in a mirror!" Donald James’ script, underlined by Gray’s optimistic score, appropriately takes the reverse view. Webb’s final thought is that it’s worth anything to get to the other side of the mirror.

Unfortunately, even after being retitled “Journey to the Far Side of the Sun”, Doppelganger failed at the box office. There has been a lot of speculation as to why the movie didn’t succeed – the films ending is a “downer” but then so was “Planet of the Apes”. The structure of the film might also have been disappointing – it seems like a lot of time is spent on the training for the mission and the abrasive state of Thinnes’ marriage when the real interest lies in what the astronauts will find on the counter-Earth. The fact that we don't immediately know Thinnes and Hendry have arrived on the Counter-Earth makes this sequence seem like even more of an anti-climax. It's only when Thinnes convinces us that he's on the parallel world that the film really gets going - and by then it's nearly over! Interestingly, John Wyndham’s “Random Quest” – adapted for the BBC’s “Out of the Unknown” in February 1969 – glosses over the hero’s journey in flashback – and the bulk of the drama rests on how he reacts to his experiences on the parallel world.

However, it’s arguable that much of the responsibility for the film’s failure lies with the distributors. Sitting on the completed movie until after the United States landed on the Moon in July 1969 can't have helped its commerciality. Rank made a half-hearted attempt to downgrade the film censorship rating from “A” to “U” (the difference between children being accompanied by an adult or unaccompanied) in July 1969 before being told it would be impossible to cut out the “A” certificate elements without ruining the continuity of the film (5). The film was subsequently given a premiere at the Odeon Leicester Square on 8 October 1969, before being put on general release opposite “On Her Majesty’s Secret Service”.

From Photoplay Film Monthly - January 1970

Many of Anderson’s core audience didn’t even know Gerry Anderson had made a film called “Doppelganger” (or “Journey to the Far Side of the Sun”) until they read about it in the publicity for his subsequent TV series UFO in the 1971 comic “Countdown”. Even though they would have needed an adult to accompany them (as with the Bond movies)at least some of the Andersons usual audience could have applied pester power if they'd known about it!

You can read more about UFO and the Power Game's influence on Gerry Anderson here