n

n

Repulsion

n

n

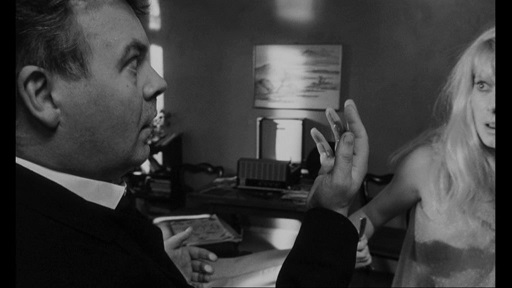

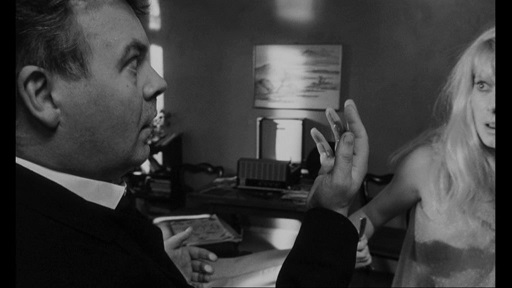

Patrick Wymark appears as the landlord of Carol (Catherine Deneuve) in Repulsion and took part in one of the most memorable sequences. Director Roman Polanski was running over time and budget just before this sequence was filmed and convinced producers Tony Tenser and Michael Klinger that he could get back on schedule. Wymark and Deneuve played the scene as if live during an almost-continuous sequence with only six or seven cuts.

Carol is a Belgian manicurist left alone in London when her sister (Yvonne Furneaux) goes on holiday to Italy with her married boyfriend (Ian Hendry). The hot summer seems to bring to a head, a mania which has been quietly simmering below the surface. Unfortunately, in his concern for her, Colin (John Fraser) mimics a vivid assault fantasy by breaking down the door to her flat. The landlord later echoes this action by forcing his way in to demand overdue rent.

Wymark portrays a sweaty, lower-middle-class opportunist, concerned at first only with money but quickly appreciative of Deneuve’s charms, offering to forget the rent if she’s “nice to him”. Wymark describes a trajectory from concern (fetching her a glass of water), to relationship-building, to assault. It’s believable and slightly farcical – at one point, after falling on the floor after trying to climb on top of her, Wymark holds out his arms as if to say – how ridiculous is this? As he moves in for a second attempt, his face hardens. Wymark’s intent would be sinister, but we already know he’s bitten off more than he can chew. Deneuve stands with Hendry’s cut throat razor hidden behind her back. We’ve already seen her kill the harmless Colin, so the aggressive landlord’s chances aren’t good.

Wymark, Hendry, Fraser and Furneaux had all agreed to perform for less than their usual fee in order to work with the hot new director Roman Polanski. For exploitation producer Tony Tenser the film proved to be a headache – he told Polanski that it was like ordering a Mini Cooper and eventually taking delivery of a Rolls Royce. Polanski held out for Catherine Deneuve to play Carol, even though Tenser and Michael Klinger had wanted Francesca Annis (star of their previous movie The Pleasure Girls). Ironically, Annis would later appear with Wymark in Tony Richardson’s 1969 production of Hamlet, before being cast by Polanski in his film version of Macbeth.

In a 1974 article for Cinefantastique , Charles Derry identified Repulsion as being part of a cycle of films which dealt with The Horror of Personality . These were horror films in which a psychological, rather than supernatural explanation is given. The sub-genre was identified a running from Les Diaboliques (1955) to Polanki’s own Rosemary’s Baby (1969)in which the supernatural finally reasserts itself. What differentiates Repulsion from many of these films is that there is no placid opening ‘normality’ that is shattered by the horror. Repulsion is very much like literary horror in which the themes are stated from the opening sentence.

The credits slide across the surface of a human eye, before the camera pulls out to reveal the blank, unblinking face of Deneuve. We see her holding on to the fingers of an elderly hand, in the same way that a child grasps a parent’s hand. The camera inspects the surface of a woman’s face, smothered in a white beauty treatment that is drying and cracking in the same way that the plaster on the wall of Deneuve’s flat will later crack. With a white towel over her hair and a white smock and blanket covering her body, the woman could be a corpse if it wasn’t for the pulse in her throat rhythmically displacing the cream. As the camera pulls back, we see Deneuve’s head nodding. The woman wriggles her fingers and demands, “Have you fallen asleep? I think you must be in love or something.” As Deneuve begins to apply nail polish, the woman declares that she’s bored with the usual shade and asks for Revlon’s Fire and Ice.

The cool red nail polish was introduced in 1952 with Richard Avedon’s enigmatic photo of model Dorian Leigh and the strapline, “for you who love to flirt with fire...who dare to skate on thin ice.” The brand sold a dream of bold, enigmatic womanhood. But as Deneuve goes out into the busy beauty parlour, she tells her employer that she thinks they’re out of Fire and Ice. Madame Denise (Valerie Taylor), bewigged, with a spider-web of laughter lines circling her mouth and eyes, hands Deneuve a bottle of nail polish telling her, ‘Put this on. She’ll never know the difference.”

The opening subtly establishes thoughts of something beneath the surface – an appreciation of the deception behind the commercialisation of sex, the impossibility of attempting to defy the ageing process. Back at her sister’s flat, we see Deneuve gaze up out of frame while her sister (Yvonne Furneaux) tidies up in the background. “We must get this crack mended,” she says with a sudden urgency, but we never see what she’s looking at and when her sister turns round to question “what?” the doorbell interrupts their conversation. The visitor is the sister’s boyfriend (Ian Hendry) whose presence (particularly his cut-throat razor in the bathroom) offends Carol. That night she tries to sleep in the heat as the sound of her sister’s guttural love-making seeps through the wall. The image of the crack recurs Carol sees a crack in the pavement and stares in fascination. Alone in the kitchen of her flat, the camera closes in on her face as a rippling noise like thunder fills the soundtrack, followed by a drumroll. Deneuve turns to look and we finally see the wall developing a crack similar in pattern to the one she saw in the pavement. Later on, when she flicks a light switch, the plaster cracks with a well-timed physical effect.

The film avoids easy explanations. At one point, Wymark picks up a photo of Carol as a child with her family. We’ve already glimpsed the photo, and at the end of the film the camera closes in on the face of young Carol, glaring at something out of shot. The significance of the photo has often been discussed, but there is no convenient psychiatrist coming on at the end to pin down the explanation. Ironically it is Hendry, who earlier said Carol should see a doctor, who ends up carrying the catatonic girl out of the flat. He almost holds her like Prince Charming and throughout the film there are fairytale allusions – Carol is referred to a Miss Muffett and Cinderella. There’s a possibility that she’s longing to remain in childhood; one of the saddest scenes comes when workmate Bridget (Helen Fraser) – who had previously been dumped by her boyfriend – tells Carol she should go out and see a movie. Carol clearly thinks she means they should go and see a movie and then bitterly realises her mistake when Bridget explains how she and her new boyfriend laughed at an old Charlie Chaplin film.

The film has a strong cast – John Fraser, always seeking to push the boundaries of conventional leading man status, would later co-star with Wymark in his final tour of Sleuth . James Villiers ( Harvey Graves in the Plane Makers episode The Smiler plays one of Colin’s obnoxious drinking buddies, while Mike Pratt (from Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased) has a small but significant role. The film is not without humour - the scene just before John Fraser’s murder is blocked out like a scene from a Doris Day/Rock Hudson movie as Fraser tries to tell Carol he loves her while a nosy neighbour watches in the background. Despite the ‘artiness’ of the story, Polanski is able to deliver solid shock effects and the film has a sustained creepiness.