SCALES OF JUSTICE

A Woman's Privilege. Writer James Eastwood. Anthony Bushell.

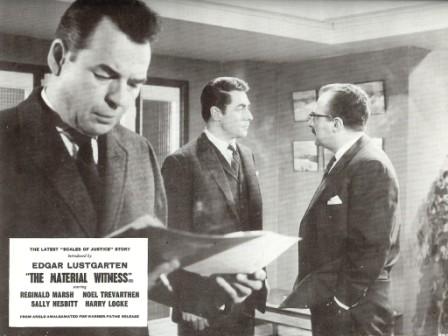

The Material Witness. Writer James Eastwood. Director Geoffrey Nethercott.

Merton Park Studios had produced Anglo Amalgamated's “Scotland Yard” series of cinema featurettes for many years, but the series had come to an end in 1961 with “The Square Mile Murder” ( by 1964 the short films would be screened on ITV under the title of “Casebook”). From 1962, Merton Park followed up with "Scales of Justice". Once again, each film was introduced by writer, broadcaster and criminologist Edgar Lustgarten, although the new series had a wider brief covering civil, as well as criminal cases.

A Woman's Privilege was the second in the series, released in November 1962. It stars Ann Lynn as Shirley Fawcett, a young woman taking an ocean cruise to get over a failed romance. While on board, she meets Joe Ashton (Bernard Archard), and a romance develops. But when the romance goes wrong, they end up in court. Eastwood's script is touching and unpredictable and comes to a bittersweet resolution. Despite being third-billed, Patrick Wymark's role as Shirley's barrister is quite brief, and the significant lines go to fourth-billed Ernest Clark as Joe's advocate. Wymark does some good glowering in reaction to Clark's cut and thrust, but in hindsight you can't help wondering if they swapped roles (or maybe Wymark had a better agent).

A Woman's Privilege was directed by Anthony Bushell, who as an actor had played Colonel Breen in the TV production of Quatermass and the Pit. Bushell had also directed Patrick Wymark in The Mindreader, an episode of ITC's Man of the World, first broadcast in November 1962. Bushell's direction is competent and assured, relating the shipboard romance and shifting locations with no indication of the low-budget nature of the production. For present-day viewers, the location filming at the petrol station owned by Joe Ashton with its thatched roof and Regent petrol pumps will have some nostalgic interest.Ann Lynn would subsequently star opposite Wymark in Freya of the Seven Isles, a BBC adaptation of Joseph Conrad's novel broadcast in January 1963. As noted, Eastwood's script was sensitive and exploited the central point of law in a convincing manner, unlike some of the later entries which relied on improbable last-minute twists.

1963's A Position of Trust features an unexpected performance from Peter Barkworth as a sleazy private eye, but unfortunately is undermined by one of the aforementioned absurd last-minute twists. Slightly more satisfying is, The Material Witness

“The Material Witness” was distributed to cinemas by Anglo-Amalgamated from December 1965 and starred Reginald Marsh as Harry Turner, a sales executive at an anonymous engineering firm. Introducing the film outside a three-storey 1950’s office building, Edgar Lustgarten describes the story as being about, “the psychological factors that exist in any firm.”

Turner is far removed from Arthur Sugden, having a southern accent, an alcohol problem and a sharp tongue towards his assistant Lewis Carter (Noel Trevarthen) when sales figures are not delivered on time. Turner suggests he should have worked on his own time to finish the figures. “If you want to go on working in my department you do as I say.” Lustgarten describes Turner as “efficient, conscientious, but a man under stress and therefore vulnerable.”

Turner has returned from a trip to the Glasgow office, getting one hour’s sleep on the plane after a heavy drinking session. He goes to lunch with client George Lennox (Hector Ross) promising a new restaurant five miles away where they can have “decent food and a sound bottle of wine.”

Racking up four drinks at the bar, steak au poivre, a “bottle of the ’27” two large whiskies and a brandy to finish off, Lennox orders a taxi but Turner decides to drive home. Marsh recreates the ponderous care of drunkenness as he pulls the table aside, bumps into another table, gets irritated when the waiter asks him if he’s alright as he pulls on his coat, and then struts over to his car before lurching off with crunching gears. As his car weaves along misty country roads, a police car pulls him over.

At a magistrates court, Turner is convicted of reckless driving and exceeding the speed limit. Because of his previous convictions, Turner is disqualified from driving for two years and sentenced to two months in prison (“an exemplary sentence”).

When he is released from prison, Turner finds that Carter has been given his job. He is moved to the research department with a cut in salary and no expenses. Even worse, he discovers that Carter has ingratiated himself with Turner’s family and is dating his daughter. His wife says she had expected him to look for another job but as Turner says, “at my age? With a testimonial from the Governor of Wormwood Scrubs?”

Turner goes to the restaurant to drown his sorrows, and there barman Sam (Harry Locke) tells him that Carter was at the bar the day Turner got arrested, and Sam overheard him phoning the police to warn them that a drunk driver had left the restaurant.

“The Material Witness” was filmed three years before the breathalyser test was introduced, at a time when drunk driving was still viewed as harmless by much of the population. As barman Sam says of Carter, “Some would say he was being a public spirited citizen..others would say he was being a louse.” The film was made in a context where lunch at the pub was an accepted part of British life up until the 1980’s. Directed by Geoffrey Nethercott, who had helmed episodes of “The Plane Makers” such as “The Trouble With Auntie”, James Eastwood’s script never addresses Turner’s drinking other than to have him say, “Why do I drink? I don’t know. But surely to God I don’t deserve this!” while waiting to go to prison.

The film is ultimately unsatisfying although it shares elements with Leslie Sands’ “A Matter of Self Respect”, and Richard Harris’ “All Part of the Job”, the need to deliver a neat resolution leads to bizarre self destructiveness by Trevarthan’s character.