The Gaudy Banner of Peter Draper.

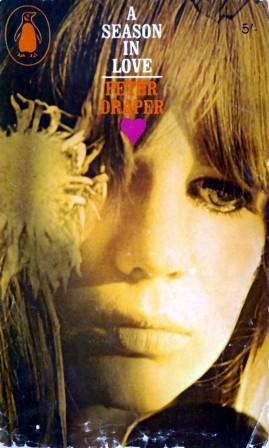

“Only the past remains whole..moving further and further away, taking our youth, our hopes, and finally love, until in time they all appear to merge…like a gaudy banner we had once tried to defend and, beaten back had to abandon..”

Peter Draper “A Season In Love”

Writer of many of the most entertaining “Power Game” scripts exploring the shifting sands of emotional relationships, Peter Draper also scripted a wide range of dramas including the Oliver Reed film “The System” and an intriguing but sadly wiped episode of the BBC supernatural series “Dead of Night”. It’s ironic that the majority of his finely-crafted scripts were never repeated and have only recently become available on DVD.

Peter Draper was born in Porthcawl, Wales on 28 April 1929. While at art school he worked with the West of England Children’s Theatre and subsequently joined the Bristol Old Vic company as an actor and stage manager.

Deciding to become a writer, Draper got a regular income from working in an advertising agency before starting the Milton Head Pottery Company in Brixham, Devon with two partners in 1950. At age 31, Draper was commissioned to write a play by HM Tennents, which was then producing drama for the new ITV company Associated Televison. The subject, Nurse Edith Cavell, had come from Dame Flora Robson, who had long wanted to play the British nurse executed for helping allied soldiers excape from German-occupied Belgium during World War One. Coincidentally, Draper’s wife was distantly related to Nurse Cavell. “…And Humanity” , starring Dame Flora Robson and Donald Pleasance, was produced as part of the “ITV Play of the Week” strand on 5th March 1958.

The success of “…And Humanity” led to a contract with Tennent’s for more ATV drama, and the Pottery business was sold the same year. Plays included “The Paraguayan Harp” (13 Feb 1959) starring future “Doctor Who” producer Peter Bryant and “Sunday Out Of Season” (13 March 1959) starring Maggie Smith as Elaine, a student who tries to forget a love affair by spending a winter weekend in a Welsh seaside town. Alec McCowen plays an intelligent young local who meets her while trying to find diversion on a damp, windy Sunday ( ATV would transmit a remake on 7 February 1965, starring Ian McKellen as Victor and Lynn Redgrave as Elaine.)

On 6 May 1960 Draper followed this with The Big Night starring Robert Stephens as Frank Rush, who is "not unhappily married" but wonders if romance is passing him by. Described as the sort of man who asks himself, "Why, when I'm over here do I want to be over there, and when I'm over there, do I want to be over here?", Frank takes advantage of his wife Mary's (Sylvia Kay)absence. He talks his friend Tom Pugsley (Barry Foster) into a night around the pubs where he meets actress Madeleine Grail (Judith Stott). Invited back to her flat, Frank discovers that her character and background is different to what he expected. Stephens praised Draper as having the knack for, "expressing odd, contradictory thoughts, and the foolish behaviour of men of all ages."

In 1961, Eyre and Spottiswood published Peter Draper’s novel “A Season In Love” . Set in the late 1950’s, it is narrated by Sam Wilson who has been working in a South African news agency job arranged by his uncle. Bored with the Expat community, he returns to London but is immediately disillusioned. His local pub has been demolished and his friend Bruno has gone off to Paris. Adding to his frustration, Sam had spent two days in Paris before continuing on to London. In the pre-mobile phone days, he had no way of alerting Bruno to his sudden return other than to send a cablegram which was delivered to an out-of-date address.

Sam also discovers that Bruno has left his long-time lover Sophy for a French student living in London. When Sam meets Claudine, he detects a hint that she may be “available” and determines to seduce her so that he can restore Bruno’s relationship with Sophy. But instead he finds himself falling in love with her.

The novel explores many of the themes that would recur in Draper’s teleplays. Wilson says of London that, “one’s love affair with a city starts coming to an end when one discovers she is a whore: that the smoky inviting eyes which promised everything can, after the first orgasmic explosion, stare at you, only distantly interested.”. This seems to foreshadow Wilder’s pronouncement in Hagadanthat “we use people up as we use up everything else up.” At one point Wilson visits the former site of the Festival of Britain which had “begun to take on the appearance of something in decay.The plaster-work of some of the gaudy set pieces left over from the Festival was beginning to show some cracks,” But nonetheless an elderly couple remark that they wish they could have come to the Festival and walk “almost reverently as though they were passing through the courtyard of a Venetian palace.” Wilson is constantly trying to recapture a past that never existed.(“I had the idea it might be able to hold open the shutter between the past and the present so that they could become one.”) His friend Bruno (who is barely seen in the novel) turns out to be a serial deceiver and the apparently idyllic relationship with Sophy was an illusion with betrayals on both sides.

Draper evokes a run-down, war-battered London, where men of a certain class live in “cheap Bayswater hotels”. At breakfast, he meets Cordingly a salesman who has, “a need for constant conversation..(he)..could never let a minute go quietly, as though he were aware of having to lull people’s discernment and that his first obstacle was to make the person he was talking to accept him. It came, I imagine, from years of selling things he had little confidence in.”

Cordingly becomes one of the most vivid characters in the book. At the end Sam reflects that Cordingly, “seemed able to bounce up from his inevitable disappointments, still believing that somewhere, somewhere, it all lay before him, that he only had to find it while our disappointments, and even achievements, gradually harden us into accepting what we’ve got.”

In 1963, Draper contributed his first script to “The Plane Makers” with “A Good Night’s Work” (27 May 1963) starring Alec McCowen as John Rodway, a junior executive whose future depends on the success of an unexpected night out with a South American woman (Erica Rogers). Draper would write two more scripts for the second series of “The Plane Makers” – .Any More For The Skylark (28 October 1963) featuring Rodney Bewes, John Woodvine and Barbara Windsor, and .Don’t Stick Your Head Out (14 October 1963) the episode which introduced Ingrid Hafner as the mistress of John Wilder (Patrick Wymark) and first explored the moral tightrope of Wilder’s marriage.

Draper would address those issues further in “The Funambulists” (21 October 1963) directed by John Moxey. The “Play of the Week” starred Francis Matthews as Michael, who has had several affairs but suspects his wife Susannah (Judi Dench) is being unfaithful. He hires detective James Stack (Peter Barkworth) to follow her, but is surprised when Stack goes further than expected. Draper told the TV Times that “Stack is one of those innocent people who get hurt by the deceptions of clever people.” He likened them to tightrope walkers or “funambulists” who “play around with moral attitudes” but may fall off the rope.

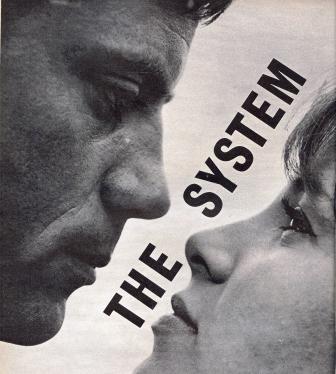

Draper was now writing “The System” for Michael Winner. Released in October 1964 (and retitled “The Girl Getters” in America) it starred Oliver Reed as beach photographer Tinker, the leader of a gang in a West Country seaside resort who compete to “make” the young female tourists. “For three months the place is thick with them. (In winter) after six o’clock there’s nothing moving in the streets at all. Everyone’s home watching telly. And the girls are the same girls you knew last year…so we make it while we can…the best girls, a different one every week if you want. “ Much like the lead character from “A Season in Love”, Reed finds his heart being broken by strong-willed model Jane Merrow.

Filmed at Brixham, Paignton and Torquay, the film (and Draper’s ) lasting legacy appears to be the West Country term “grockles” used to describe tourists. Opinions are divided as to whether Draper invented the name, or simply picked up a very localised slang, but the term has persisted to this day. .If you can struggle past the disabling pop-up advert’s typical of local newspaper websites you can read more and see clips from the movie via this article on The System.

In 1965, Draper contributed two episodes of “Front Page Story”, Wilfred Greatorex and Rex Firkin’s follow-up to “The Plane Makers”, which took the same approach to “The Globe” (the fictional counterpart of the Daily Herald/Sun which Sir Gerald Merle had been a director of in “The Plane Makers”). One of Draper’s episodes featured Basil Henson as reporter Sandy Warren (both actor and character would return in “The Power Game” episode “Confound Their Politics”). The second, titled “The X-Men”, featured Rupert Davis as Felix Rakstro, an acquaintance of reporter Denny Tarrant (Derek Godfrey) being investigated by the fraud squad.

In late 1965, Sir John Wilder returned in “The Power Game” and Peter Draper contributed seven episodes, many of them exposing the tangled love lives of Wilder, his wife Pamela Wilder (Barbara Murray) and their lovers .Hagadan (20 December 1965) introduces George Sewell’s character of engineer Frank Hagadan, but the first part has the atmosphere of a standalone play about an affair as Wilder spends the evening with his new mistress Susan Weldon (Rosemary Leach). The Crunch shows Wilder’s unexpected distress when he discovers Pamela’s affair with Hagadan.

Not surprisingly, Penguin Books found this an opportune moment to release a paperback of “A Season In Love” .

With the suspension of “The Power Game”, Peter Draper continued to write TV plays such as the “Half Hour Story” on 13 September 1967. Titled “Bug” it starred Bob Monkhouse as radio ham Q.P.Jakes who suspects his wife of being unfaithful and attempts to hire detective R.J. Smellie (Bill Owen). But the detective takes offence at the electronic recording devices which Jakes has been using to track his wife.

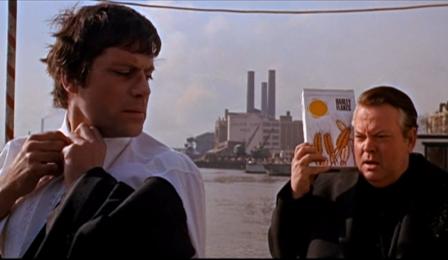

Draper also re-united with Oliver Reed and Michael Winner for “I’ll Never Forget What’s’Is Name” (1967). Reed plays Andrew Quint, an advertising executive who takes an axe to his desk at Orson Welles’ agency to go back to a small literary magazine run by old university friend Norman Rodway.

Quint’s disillusion reflects a comment in “A Season In Love” that, “We were living in the age of consent, of people agreeing to things they didn’t understand..the age of the slick operator who was already preparing the next item so that nothing last long enough for anyone to understand it, or even to assess it.”

With overtones of “The Prisoner”, Quint eventually discovers that the literary magazine and the entire building has been bought up by Welles who is installed in a luxury apartment on the top floor. Quint agrees to return and direct a big budget advertising film for a competition. Although his movie is a surreal attack on commercialism, it wins the competition ,perhaps because Welles has fixed the jury or perhaps because no-one cares to understand the message. The irony of Patrick Allen doing the voiceover for Quint’s film is not just that Allen set up his own company to make commercials, but also that Allen was later revealed to be the “voice of doom” on the public service film that would have been broadcast in the event of nuclear war.

Filmed in “Swinging London” the film shares some quirks with “Blow Up” and “If” Frank Finlay appears in a surreal flashback as a Headmaster telling young Andrew that, “Games are the essence of life and the value of team games is that they teach us to live together…the man who is not interested in sport is not interested in living with other people.”.

Reed’s tentative romance with secretary Carol White is the most engaging part of the movie, but with ex-wife Wendy Craig and former mistress Marianne Faithfull the most overwhelming impression is that Quint has “never had it so good.”

Despite stylish direction from Winner, the film failed to make a lasting impression perhaps because most cinema audiences found it hard to feel sorry for people who earn a fortune but lose their soul when there’s plenty of opportunity to lose your soul without much reward.

In 1969 Draper contributed three more scripts to the third and final series of “The Power Game”. In The Goose Chase Draper creates the memorable character of Professor Mobbs who is attempting to recruit Wilder’s assistant Lincoln Dowling (Michael Jayston) to MI6.

Following the end of the The Power Game, Peter Draper contributed to Wilfred Greatorex’s series about arms dealer “Hine” (1971) and also branched out to BBC series such as the original “Poldark” (1975).

He also wrote “Death Cancels All Debts” – a now wiped episode of the BBC 2 horror series “Dead of Night” (1972) in which a young writer tries to interview a great British writer (Sebastian Shaw) now sunk in alcoholism and encroaching dementia. The writer and his wife are haunted by a presence which manifests itself as snatches of “Fur Elise” played on a piano – a presence which may hold the key to the literary mystery behind the “great man’s” works. The question raised by the play is how much a ghost may owe to our memories and what might happen if the memories are confused. Despite being wiped, the play made an impact on those who saw it.

In the same year Peter Draper contributed a play called “A Persistent Coffin” to the BBC 1 anthology series “The Man Outside”. This was spun off into a six part BBC2 comedy series “The Perils of Pendragon” broadcast in 1974. Set in the Welsh village of Pendragon, it starred Kenneth Griffith as Isaac, a sexually repressed shop-keeper deeply suspicious of the sins of the flesh and John Clive as his mercenary Welsh nationalist nephew Rosko. It appears to have evidenced a familiar dark humour (“One day my boy, you are going to find yourself particularly famous around these parts as the victim of a particularly nasty unsolved murder,” but references to contemporary politics seem to have backfired when one of the six episodes was deemed too sensitive to broadcast near the 1974 general election. Produced by Derrick Sherwin (who had produced "The Man Outside") the series was screened opposite "Kung Fu" and "Billy Liar" on ITV which probably didn't help its chances of success. All tapes were sadly wiped by the BBC. Following the death of Kenneth Griffith, co-star John Clive appealed for off-air tapes, writing,”Kenneth Griffith always brought something fresh to the take…Kenneth couldn’t abide repetition. I know the BBC wiped it soon after so it has never been shown since despite the universal praise heaped on it. Peter Draper was the writer that gave us the tools to be good.”

Peter Draper’s final TV script was “the Damask Collection” an episode of “Jemima Shore Investigates” (1983) starring Patricia Hodge. He died in Exeter in 2004.